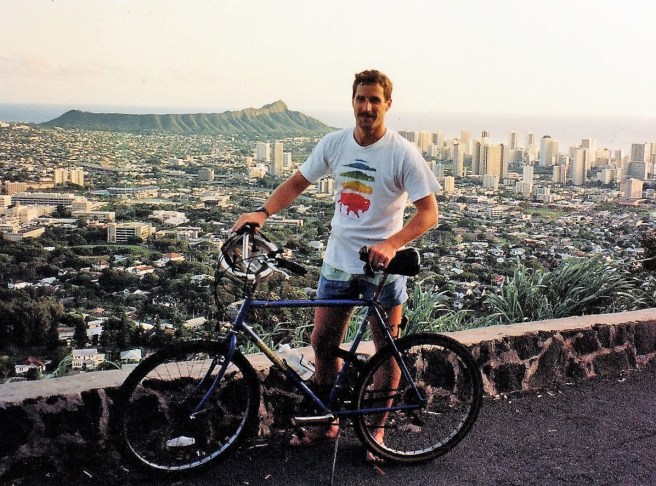

Authors Note: In 1992, the East-West Center, a federally funded research institution located on the University of Hawai’i in Honolulu awarded me with an academic scholarship for four years of graduate study and field research towards the degree of Doctor of Public Health.

I was also recruited for a summer research project with the Thai Red Cross Society in Bangkok – interviewing street children, residents of crowded communities (a.k.a. ‘slums’) and social workers to assess the current and future impact of HIV/AIDS on children in Thailand, which also helped to refine the focus of my doctoral research project.

Klong Toey Slum, Bangkok

I met Lee at a public swimming pool near my apartment in Bangkok and she graciously offered to assist me with my summer research project. Her excellent English, keen interest in HIV/AIDS and wonderfully supportive and cheerful companionship were a real boost.

Riding hot crowded buses roaring through the capital city’s choking air pollution and notorious traffic to and from work, our days were spent conducting interviews in the hot, stifling crowded urban slums. Built on a swamp, Bangkok’s largest slum “Klong Toey” is home to over 100,000 residents, crammed into roughly one square kilometer of sludge, rubbish and sewage. Many of the tin-roofed houses are on stilts over stagnant, polluted water, and the area is prone to flooding particularly during the monsoon season.

Seated cross-legged on the floor, there was an easy-going village feeling even in those cramped urban quarters as most of the residents were poor rural migrants who had come to the city to find work. The latest fad among the youth was glue sniffing and many we came across were lost in a glue-fume stupor.

Balancing on rotting boards above the stinking swampland, we made our way along the narrow, broken walkways.

Then one day when we arrived a crowd had gathered to receive soap and rice from a local relief agency – twenty percent of the slum had burned to the ground the previous night. Two hundred eighty families suddenly homeless – no food or money, everything lost. A young sex worker we interviewed echoed the sentiments of many of the slum residents: “Of course, AIDS can kill you in a few years, but I have to feed my family today.”

A late afternoon downpour jammed the traffic to a standstill. Walking was going to be faster than to creep along in a sweltering traffic snarl, so we hopped off the bus and ducked out of the rain and into a food stall for some soup to wait out the storm.

At home, a cold beer washed down the urban residue. Sharing some late season sweet mangoes, sticky rice and coconut cream, Lee rescued me from my self-destruction and despair and helped translate our taped interviews with social workers, sex workers and drug users.

Yes, all of this and Willie Nelson (“Blue Skies”) on the radio helped put a guy in a jolly mood. It was really getting better, as long as I didn’t go insane! A final trip to the beach left us tanned and refreshed. And at last a focused dissertation topic on a meaningful and pressing issue was finally materializing.

Abandoned Children and HIV/AIDS

With the course work finally done, and my ABD “All-But-Dissertation” certificate in hand, I departed Hawai’i in July 1993 to begin nine months of independent field research in northern Thailand to examine the factors underlying the recent escalation of abandoned newborn infants in the northern city of Chiang Mai, with particular attention to the rapid spread of HIV, which was devastating the northern part of the country.

Using participatory urban and rural appraisal techniques to assess the magnitude and nature of problems within the context of rapid social change, the research aimed to inform effective policy and planning to address the underlying conditions within which child abandonment was occurring — including options for prevention and community-based management of abandoned children.

The precise number of children abandoned in Thailand at that time was not known, although estimates based on institutional data suggested that more than 2,000 children were abandoned each year in 17 northern provinces – some of the poorest parts of the country.

But this was likely just the tip of the iceberg, as survey research had also found increasing trends of child abandonment by their mothers in hospitals shortly after delivery, as well as children born elsewhere and later deserted at hospitals. At that time, just one quarter of those in need had access to child welfare services.

When I began my research, there was one orphanage in Chiang Mai, Thailand’s second largest city. But within a years, the number of orphanages had grown to six to manage the growing number of abandoned children.

As young people were increasingly moving to towns from their home villages for work or school, the risk for unintended pregnancies increased dramatically among the unmarried young, often poor women who were then being left alone by their partners when becoming pregnant.

So, it was in desperation that these women — typically poor, alone and too ashamed to return to their village as a single parent — would present for an emergency delivery and then escape, leaving the baby on the table. Far from being a malicious act, her rationale was that the clean, modern ‘baby home’ or hospital would surely be able to provide a better future for her child than she could.

Orphanages or “Baby Homes’ typically cared for orphaned boys and girls up to age five. But by age six, the orphaned girls would all have been adopted, leaving only the boys in what are called ‘Boys Homes’ until they are old enough to legally go to work.

Interestingly, baby girls were more highly coveted than boys by Thai adoptive parents — typically older, their own children grown and gone. A girl was considered less trouble than raising a boy, and also more likely to stay home to take care of the parents in their old age.

Stay tuned for Part Two, coming soon!

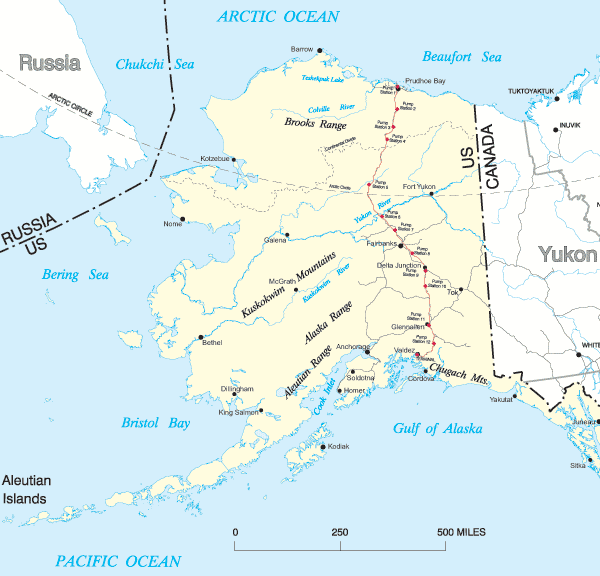

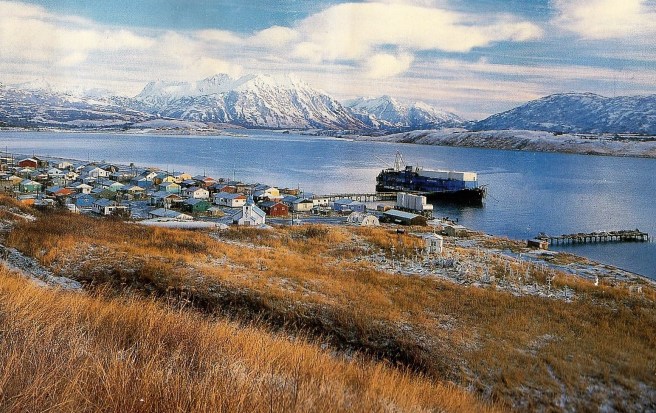

Flying on to Alakanuk village on the Lower Yukon Delta we enjoyed spectacular scenery by light aircraft – flying over thousands of mirror-like ponds and squiggly waterways flowing through the multiple shades of greenest tundra feeding the Yukon-Kuskoquim Rivers and flowing out to the Bering Sea and on to Siberia.

Flying on to Alakanuk village on the Lower Yukon Delta we enjoyed spectacular scenery by light aircraft – flying over thousands of mirror-like ponds and squiggly waterways flowing through the multiple shades of greenest tundra feeding the Yukon-Kuskoquim Rivers and flowing out to the Bering Sea and on to Siberia.

Indeed, the people I met were exceedingly warm and gentle, and perhaps the most spiritual people I had ever known. When asked to describe themselves, it was always a ‘circle’ – balanced and in harmony with the universe.

Indeed, the people I met were exceedingly warm and gentle, and perhaps the most spiritual people I had ever known. When asked to describe themselves, it was always a ‘circle’ – balanced and in harmony with the universe.

So it began – my tumultuous re-entry into the Western world as this ‘primitive man’ so to speak, prepared to ‘leave the trees’ – as illustrated in a typical Far Side cartoon panel showing a cave man clinging desperately to a tree at the edge of the forest as a truck stood by waiting – presumably to take him to the city.

So it began – my tumultuous re-entry into the Western world as this ‘primitive man’ so to speak, prepared to ‘leave the trees’ – as illustrated in a typical Far Side cartoon panel showing a cave man clinging desperately to a tree at the edge of the forest as a truck stood by waiting – presumably to take him to the city.